Header image is A decaying wharf in Liverpool by Neil Howard used under license CC BY-NC

You might be interested in the prior installment of this series, Hockey Pool Part 2: From the draft through the playoffs.

Preparing for my second year, there are good reasons why I think I’ll have the best chance at winning:

- I can now play the tactics of setting a line-up. I think I can do this about as well as anyone in my pool

- I’m going into the draft with two extra high picks

- I’m going to draft better than anyone else (bold statement, but if you read long enough you’ll see why)

There are good reasons why I think I’m unlikely to win the pool:

- My keepers aren’t the best, and I can’t fix that. With three keepers each, my two first round draft picks are really like two fourth round picks from last year

- There are at least a couple of other very good players. I can blow past the bottom of the pool, but at the top I’ll have company

- There’s a lot of randomness

Let’s go into detail on that last point. Even if I have the best overall team (which I expect I will), in any given week I could lose, especially to one of those other good teams. I have to win three playoff rounds to win the pool. Even if I had a 75% chance of victory in each, my probability of winning all is only 3/4 to the power of 3, or 27/64 – distinctly less than 50%. This is another way that the pool mirrors reality, where winning the Stanley Cup requires a lot of luck and peaking at the right time. It would be boring if it was entirely deterministic. Until I actually analyze how much random variation there is, I don’t have a good intuition on what win probabilities I would have in each round. Potentially I can look at how dominant I was in the regular season against teams of that quality, and make an approximation. But if anything I expect my odds are worse than this generic estimate, because the second best team is probably not far behind a 50% chance of beating me themselves.

Let’s Talk Prediction

Regardless of how I approach the rest of the problem, I’m going to need predictions. Going into the draft I need to have an idea of how each player will perform on all of their stats for the upcoming season. Otherwise, what’s the point?

Perhaps the easiest way to approach this would be to find published predictions from other draft sources, and just use those. The disadvantage of this method might be challenges automating it and having it work every year. Another simple technique would be to take every statistic from last year, or the career average, and presume that the value in the year after would be the same. Conceptually, this isn’t too far off from what I did. I chose to build models predicting every stat for every player, based on their past statistics. I tried to keep this as simple as possible.

First, I had to get the data. I had to find a source with not just the basic stats like goals and assists, but also less tracked stats such as hits, blocks, and faceoffs. Eventually I found my source in Yahoo, and with a small Python program I had all of their data downloaded. Then I wrote a program to import all of the data into SQLite databases, including a final merged database and a corresponding CSV file. Python is very practical for these types of tasks, including having easy network and parsing abilities. SQLite is easy to setup on new systems (has no server and needs no configuration) and easy to migrate databases (they’re just files stored on disk). This makes it handy for these kind of simple single-user problems.

I then imported the data into R and continued my work there. Why the change of languages? Python does indeed have modelling features and a vibrant community which advances them, but R still has a big advantage in this area. At first I was not sure which modelling technique I should use; R gave me the most flexibility since it supports the most techniques and usually requires the same data layout for each. However this advantage isn’t so substantial that it will always outweigh other factors. With some of the challenges I faced later in the project I cursed myself for the decision to leave Python.

I didn’t want to spend a lot of time on the modelling, so I didn’t. Partially this is because, like the projects we undertake in the real world, we have limited resources that we must use wisely. In this case my resources are my own time and my available processing power. I want to simplify the project wherever possible such that I will actually get it done in time for the draft (accounting for my myriad other ways to consume my time along the time). Then I want to use that time as wisely as possible, investing energy where I’ll make the biggest gains.

The other reason is more straightforward – I just didn’t find it interesting. Predicting things is part of my day job. Let’s keep it short and sweet so we can move on to more unique aspects of the problem.

My R code imports the data into a time-series data structure (a pdata.frame) where each row (or observation) is a player season. Then it generates more columns (or variables or vectors) that contain per game versions of each stat, career averages, and lagged values (for up to the number of seasons available). With a bit of data analysis I decided I wanted to predict per-game values, and then create a season estimate of each stat by multiplying by my prediction of games played. Then I built automated LASSO models predicting each of my per-game stats. For every stat, the career average or value in the preceding year for the same stat are probably the most common predictors, but a selection of others may have a small effect too. For some less obvious statistics, other variables outside from the lagged value have more weight.

The advantage of this method is speed, both of development and run-time. The entire process is automated and runs in seconds. I can update with another season of data and run it again. Presto. There are a lot of disadvantages, too. LASSO might not be a good structural choice for all of my targets. My errors across models are likely to be correlated. My models won’t pick up a broad series of non-linear effects. I haven’t applied an ageing curve to the population, so my games played estimate is quite lazy (other stats are likely to be affected too). For young players, minutes per game might increase above and beyond increases in games played. My model, unlike expert forecasts, does not incorporate the effect of trades, or moving up or down the depth chart, or being shifted to the wing, or a multitude of other factors that won’t be evident from past data.

From that long (but probably incomplete) list of issues, I could be tempted to either give up or obsess (more) on how to get closer (or just…close) to perfection. But all that said, the models work alright. Model coefficients seem reasonable, predictive accuracy is solid, and overall the answers seem to make sense. There’s tons of room for improvement, but there’s also tons of time to work on other parts of the project.

How to Evaluate a Team

Presume your predictions are finished. Congrats. Now, how do you use them?

Maybe you’re thinking that when your turn in the draft comes up, you’ll pick the best player available. Great. That’s what everyone wants to do. How do you know who’s the best? At the margin, any two of your candidate players will have trade-offs between them. One might have good hands, generating goals and assists, while the other is a bruiser, accumulating penalty minutes and hits. Goal scorers are stars, but here all categories are treated equal. How do you decide which player is best? Further, in general forwards will pick up more stats than defencemen. Yet you still have four defenceman spots in your lineup to fill. Even if the best available defenceman is worse than the best available forward, the gap between the defenceman and the rest of the field may be larger. How do you make these trade-offs?

Even without making decisions, how do you value your team as a whole? Again you probably won’t be better than another team in every category (unless they’re a certain friend of mine and truly bad at drafting…).

One way we could go about estimating this is by predicting the season. For each of 22 match-ups (twice against each opponent), predict your stats and your opponent’s. Every category has a rate of occurrence. You might expect a handful of goals, lots of faceoffs, and approximately zero shorthanded goals. Account for the distribution of games played, and the error rates of your models. Calculate a probability of winning each match-up, then a probability of winning the league. You could calculate numerically or simulate. It’s not a bad technique – maybe I’ll hold onto this for later.

That’s not what I did, because again I want to simplify. I wanted to find a suitable deterministic (and easy to calculate) function that would have a few pleasing features:

- It would incorporate the predictions for every stat for every player

- It would incorporate predictions for the opposing teams

- Each statistic would be valued by its own scale – faceoffs come in multitude, goals are rarer

- It would incorporate how predictable each statistic is

- The value would be diminishing in how large my lead (or deficit) is in each category. If I have lots of the top faceoff men, I’m going to win the category almost all the time. Adding someone else who is good at faceoffs might not make a difference at all. I only care about winning or not winning the category in each match-up, not the absolute amount. Likewise, if none of my players take faceoffs, I’m going to lose it every time, so adding one good centre doesn’t help. However, if I’m about average at a stat, adding a player who is good at it might help me win the category much more often

That last point is a little more nuanced, and it incorporates how the value of your team is dependent on the players on the other teams.

I created a small set of similar metrics. My favourite is calculated as follows:

- For each category, I sum up my team’s predicted values

- Then I calculate how many standard deviations my team is from the average – this is how I treat each category as equally valuable and on its own scale

- Then I scale that by how well I can predict the statistic, so I value a category more if I’m more likely to predict it well

- Finally, I take the square root (of the absolute value, which is relative to the average) and apply the correct sign. The square root implies that I care most about marginal changes at the average.

This statistic fits my needs, with the caveat that it is not grounded in any particular data. For example, why square root, and not another function that has a similarly diminishing effect over time? If I could pull data on who wins and loses thousands of hockey pools, I could optimize my statistic to better correlate with actual outcomes. Alternatively I can use the method described earlier to simulate many pools, and see which of several statistics best correlate with winning the pool. But again, considering I’m playing 11 other guys who probably aren’t trying nearly this hard, I can move on to other parts of the problem.

Optimizing Player Selection

Notice that the proposed criteria above is a team-level stat, not a player-level stat. If I knew who all the other players on my team will be, I can pick the player who will most increase that stat. Unfortunately, I don’t. Further, it’s not only contingent on who I choose, but also who the other drafters in the pool choose.

I built a draft engine. The general setup I used was to:

- Initialize the draft with a draft order and a set of teams

- Each team is of a S3 class drafter. A drafter holds state of who is on the team, and the criteria for how to draft

- The engine iterates through the draft, giving each drafter a turn to select one of the remaining players

This is fundamentally iterative, but such is the nature of the draft. Everyone picks players in turns, and who they pick is conditional on who has already been picked.

The drafter class has some constraints. A drafter will fill out his team, with every position filled and also with bench players. This implies that only so many players will be chosen at each position. This creates significant complication, because many players qualify for multiple positions. For example, Patrick Sharp qualifies as both a centre and a left-winger, meaning you can slot him into either. The ability to do so gives you more flexibility to choose other players afterwards – if I’ve picked Patrick Sharp, I can pick two other centres and a left-winger, or one other centre and two left-wingers. Further, because of the bench there are far more valid permutations.

There are two players who are particularly advantageous to have because of this: Dustin Byfuglien and Brent Burns. They can fit it in as defencemen and also as wingers. Byfuglien in particular has had seasons where he’s picked up a lot of points as a winger, yet can be used as a defenceman in your lineup to get another forward in. There’s a value in lineup flexibility.

Yes, this guy

5 for joking from jakarachuonyo used under licence CC BY

The drafter class confirms that a player can fit into the team, that you can allocate him into the existing line-up without having an extra player who cannot fit into his position nor be added into the two bench spots (because they are already filled). This is done with a bit of logic, but it also (in my case) involves the ugliness of hardcoding which players are valid at which extra positions.

There are different types of drafters. The default drafter uses pre-draft published rankings as his criteria, meaning he picks the next available player. I chose this after identifying high correlation between the draft order in my pool and the pre-draft rankings I found on a website (not on Yahoo, though, because I couldn’t retroactively find them). Presumably the pre-draft rankings I found are relatively similar to the ones used on Yahoo, which players use as a reference and auto-draft from if they are not present. This correlated the highest with how my league drafted, but that observation would not hold for a smarter pool, since these rankings are general and aren’t directly based on our pool’s category structure.

A child class of drafter is the smart_drafter. The smart_drafter uses one of several player-level statistics meant to mimic the team-level criteria. For the moment I have the smart_drafter weighting all categories equally by averaging the player’s z-score across all categories, and adjusting for the predictability of each statistic. When I run simulations with drafters and smart_drafters, the smart_drafters do quite well on the final team-level statistic.

The key limitation with the smart_drafter strategy is that, well, it isn’t that smart. It knows nothing of how the other teams are going to draft. Its strategy would be optimal if everyone had the same criteria, in which you always want to pick the best player. But this isn’t the case. On the contrary, imagine the case where the rest of the league drafts according to the pre-draft rankings. Some of the players you want might never even be drafted. Others will be drafted, but underrated by their owners. You could potentially do better by also drafting by the pre-draft rankings, and then just trading the most overrated players for the most truly valuable players.

Aside from the practical constraint that many players hesitate to make trades or are not very observant of the pool, there’s another danger in that strategy too. It’s that you will underestimate your opponents. It only takes one of them being smarter than the pre-draft rankings for your strategy to be ruined. If just that one player drafts like a smart_drafter and knows the value of players, then he’ll start with a better endowment of players and I’ll be unable to acquire the undervalued players that I want. Further, just because most opponents drafted by the rankings last year doesn’t mean they haven’t learned something in between (learning through losing is a good way to limit the amount of losing you do).

So let’s talk a little bit about another drafter child, the simul_drafter (or “Sim” for short), and how I designed her. Sim can, at each pick, simulate the rest of the draft. Then Sim calculates how far ahead or behind our resulting team is, by our team-level metric, versus the best other team (I could compare against average, but really I want to be able to beat the next best team). If I do this across a selection of players, I can figure out which one resulted in the best overall pick. This automatically accounts for the need to fill roster spots with different positions, since all of the ensuing teams have to be valid. You can calibrate the simultation by assigning different drafter types to your opponents, or potentially update those as the draft goes on and you identify how calculated they are at drafting. That could possibly use Bayesian updating to classify likelihood of acting as a drafter or a smart_drafter.

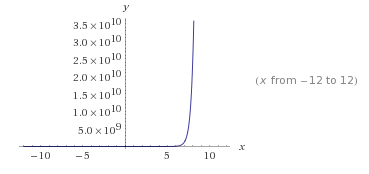

The problem with Sim is computation. To simulate your current pick, you have to simulate all of your future picks. If each future pick also performs the simulation, then this will grow very quickly. If you want to evaluate, say, 20 potential picks, across 16 rounds, then you will need to evaluate 20^16 selections (as well as letting the other drafters make their picks in the meantime, which even if entirely deterministic with pre-defined drafter types, will still add computation time).

This is one of those times where exponential growth is a bad thing

This is one of those times where exponential growth is a bad thing

I did at first build Sim this way, knowing that I would only be able to use her to some depth of players and some number of rounds. Yet I was surprised to see how slow and limiting it really was. This is especially a problem because our draft choices are timed, we only have a few minutes to make each pick. I could partially improve this with parallelization, but this is challenging because of the iterative nature of the problem. Trying to avoid making too many assumptions about the reasons behind my slow code, I did a bit of profiling. I used R’s Rprof() function, with function and line profiling, to identify the slowest (or most hit) pieces. With a few logic improvements and data structure modifications for quicker accessing, I was able to make Sim run about four times faster. Which is not nearly enough. For exponential problems, I need exponential speed-ups. Put some zeroes on there. 100x or 1000x would be a good start.

The biggest slowdown is R itself. I found that each selection itself was just taking far too long. I should be able to do hundreds of thousands of them every second. But R really is not that fast at even accessing entries in data frames. R is at its best when we can vectorize everything, but fundamentally I’m limited to iteration here. I do only have a layman’s grasp of R, but there’s no reason it should be quite this slow. I seriously considered rewriting the draft engine in C.

But wait! Let’s stay true to my principles of simplifying the project where possible. I don’t want to invest a disproportionate amount of project time into optimizing one aspect, when there are many other elements that I can improve too. Plus, I don’t want to unfairly disadvantage my opponents (who am I kidding - of course I do!). Instead, let’s only simulate the top round or two every time, on the assumption that I draft as a smart_drafter for the rest of the draft. If I simulated 20 picks each time for one or two rounds, that would only be 20 or 20^2 paths, instead of up to 20^16.

So there we have it. I made my drafting process much more feasible, by simulating less rounds and making a simplified assumption for the remaining ones. I call this simul_drafter_light, the beautiful child of simul_drafter and smart_drafter. I then built a little user input loop for running the actual draft. There are lots of little details about how that works, like how my simul_drafter_light recursively pretends its a smart_drafter, but those things are for a future post where I don’t keep the code hidden away. The code runs very fast, well within my time thresholds, and I’m not going to add any parallelization because I’m not convinced that the added complexity will translate into much additional value. There are more nuances I want to add in for next time, but I’m fine with going through the draft with this setup and reevaluating afterwards.

Good luck in your pools!

You might be interested in the next installment of this series.