Header image is . by carmen_d_cluj used under license CC BY-NC

The setup

Note: My title is playfully exaggerated. I think both the Pew study and the Atlantic article are mostly well-reasoned.

In The Surprising Reason Why More Americans Aren’t Going To Church, Emma Green of The Atlantic reviews a recent Pew study on religious attitudes in the United States, following up on an early study.

While I have a number of statistical criticisms of the Pew study, I don’t really want to dig into them, because if it feels like work writing it then it probably feels like work reading it, too. Instead I want to focus on one particular part that drew my attention, where it’s easy to misinterpret.

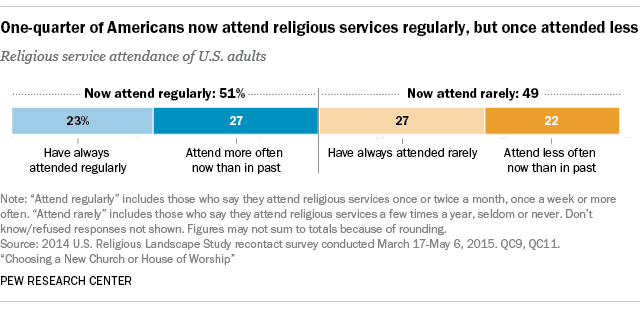

Green says “in other words, about quarter of Americans have gotten more active in their religious communities in recent years, not less” which comes from this chart in the Pew piece:

The point I want to make is that attending church more often in the past, and attending church less often in the past, are not mutually exclusive.

Say what?

You have to look at how they asked the questions. Those four bars are not from one question. Instead, there was a follow-up to the first question, and the follow-up differed by how they answered the first one. Respectively, they were asked “whether there was ever a time when they attended religious services less often than they do now” or “whether there was ever a time when they attended religious services more often than they do now.”

They’re essentially asking the regular attendees if they’re not at a lifetime minimum, and asking the rare attendees if they’re not at a lifetime maximum. Which is quite different than asking about being higher or lower than lifetime average.

Here’s an example of how you can be both. Let’s take a fictional character and name her Melissa. When Melissa was young she went to church twice a week with her devout grandmother. When she was in her 20s, she was busy and rebellious and didn’t go at all. Now she’s married and has a routine to her lifestyle, and takes her kids every Sunday.

There was a period in Melissa’s life when she used to go more often than now. There was also a period in which she used to go less often.

The tone of The Atlantic’s article suggests this is about current religiosity. But it might just be about within-lifespam variance. This is visible in the list of reasons that people gave Pew. Green discusses this, but doesn’t really hit on the implication of what this means for comparing the numbers.

Fair enough, you might say, but shouldn’t that effect balance out? No, not necessarily! Because if the religious population is older (which the earlier Pew study says it is), then they have had longer time to have a different religious minimum than the non-religious people had to find a different religious maximum. Note that the weighting used does not protect against this problem.

How to make more interesting conclusions

It may still be true that people are the U.S. religious population is becoming more devout or participatory, to a greater extent than how those who don’t attend church are becoming less so. But it still doesn’t tell us whether anything has changed from the past. If people become more religious as they age, then you’d see this pattern too, regardless of how this differs from prior generations.

You know what would be more compelling? The same data, repeated many times from separated surveys from every decade. Rather than one telephone survey with a 3.9% cumulative response rate, compare different time periods directly. And show me all of the same comparisons by age range.

Keep collecting data, and please share it so that people can explore different hypotheses!